The Mall, Central Park. www.timkang.com

The grandest of the U.S.'s outdoor public urban spaces, Central Park has welcomed the city's residents for more that 150 years. Covering 843 acres, the park reaches up through the middle of the borough, stretching from the top of Midtown to the base of Harlem. Designed in the 1850s by Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux, to capture the feeling of wilderness in the middle of the city, the park's natural environments today thrive with flora and fauna. During our time in the park, we will only sample a tiny portion

of the park's features.

Some notable attractions we will not see (and which you should return to enjoy, during your time at Drew) are:

Belvedere Castle (Mid-park, 79th St.)

Central Park Zoo (East side, 63rd St.- 66th St.)

Conservatory Garden (East side, 104th St. - 106th St.)

The Dene (East side, 66th St. - 72nd St.)

Glenspan Arch (West side, 102nd St., east of The Pool)

Harlem Meer (East side, 106th St. - 110th St.)

Iphigene's Walk (Mid-park, 79th St.)

Naumburg Bandshell (Mid-park, 66th St. - 72nd St.)

Osborn Gates (Fifth Ave & 85th St.)

The Pool (West side, 100th St. - 103rd St.)

The Reservoir (85th St. - 96th St.)

Seneca Village Site (West side, 81st St. - 89th St.)

Strawberry Fields (West side, 71st St. - 74th St.)

Umpire Rock (West side, 63rd St.)

Vanderbilt Gate (Fifth Ave. & 105th St.)

Wollman Rink (East side, 62nd St. - 63rd St.)

Central Park Itinerary

1. Columbus Circle entrance

2. Literary Walk and The Mall about | map

Named for the four statues of literary figures grouped together in the park's south end, the Literary Walk anchors the south end of the Mall. Covered by a graceful canopy of curved elm branches, The Mall is an icon of Central Park, and its only straight-line pathway.3. Bethesda Terrace about | map

Perhaps the most famous location in Central Park, Bethesda Terrace has served as the heart of the park since its redesign by Olmstead and Vaux in the 1850s.4. Angel of the Waters about | map

At the center of Bethesda Terrace, the statue, Angel of the Waters, depicts the blessing of the waters of Bethesda in the Gospel of John.5. Ramble Stone Arch about | map

One of 36 bridges or arches in the park, the Ramble Stone Arch stands in the middle of the park's main tangle of wild trees and shrubs, The Ramble.6. Central Park West & American Museum of Natural History

We'll exit the park at W. 77th St., and walk north along Central Park West, in front of the American Museum of Natural History, another of New York's very famous museums.7. Lunch at Firehouse Tavern, 85th St. & Columbus Ave. (menu)

8. W. 85th Street Entrance to Great Lawn

Entering the park at 85th St., we'll cut southeastward across the park, along the edge of the Great Lawn (map), making our way to E. 80th St. by way of The Obelisk.9. The Obelisk (Cleopatra's Needle) about | map

Dating to 1500 BCE, the obelisk was transferred to New York between 1880 and 1881.

10. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Met Assignment

About the Met | The American Wing | Korea & Côte d'Ivoire

Western Master Works | 20th-Century American | Special Exhibits | Floorplan of the Met

"The Metropolitan Museum of Art is one of the world's largest and finest art museums. Its collections include more than two million works of art spanning five thousand years of world culture, from prehistory to the present and from every part of the globe.

Founded in 1870, the Metropolitan Museum is located in New York City's Central Park along Fifth Avenue (from 80th to 84th Streets). Nearly five million people visit the Museum each year.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art was founded on April 13, 1870, 'to be located in the City of New York, for the purpose of establishing and maintaining in said city a Museum and library of art, of encouraging and developing the study of the fine arts, and the application of arts to manufacture and practical life, of advancing the general knowledge of kindred subjects, and, to that end, of furnishing popular instruction.'1

This statement of purpose has guided the Museum for more than a century.

The Trustees of The Metropolitan Museum of Art have reaffirmed the statement of purpose and supplemented it with the following statement of mission:

The mission of The Metropolitan Museum of Art is to collect, preserve, study, exhibit, and stimulate appreciation for and advance knowledge of works of art that collectively represent the broadest spectrum of human achievement at the highest level of quality, all in the service of the public and in accordance with the highest professional standards.

September 12, 2000"

1Charter of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, State of New York, Laws of 1870, Chapter 197, passed April 13, 1870 and amended L.1898, ch. 34; L. 1908, ch. 219.

During our visit to the Met, each student will be asked to view several specific collections, and to observe various artworks for later reference in class work.

First, please select three works of art from the museum's various collections that capture your interest. Based on your selections, you will prepare a five-minute oral presentation describing and interpreting these objects, to be delivered in class on Monday, August 23rd. Select one object from the American Wing, one object from the Met's collections of non-Western art, and one object from the classical European masters.

Second, students will prepare a group presentation in groups of 3, describing and interpreting one of the museum's special exhibits, as noted below. To accomplish that task, each group is asked to select one of the three special exhibits.

Third, all studemts are invited to visit the Arts of Korea gallery and view the artworks from Côte d'Ivoire listed below. Reflect on the presentation of these objects, their inclusion in a U.S. museum—presumably for their representative status as markers of cultural specificity—and the "accuracy" of their portrayal of what might (or might not) be a familiar cultural context to you.

Finally, it is very important that each student visit the American Wing's Engelhard Court, paying special attention to the exhibit of Tiffany windows and decorative arts, and the Karl Bitter pulpit and choir rail, both prominently displayed in the court.

Beyond these four required tasks, explore as much of the Met as you can. With such vast holdings, most New York museum enthusiasts even find it difficult to visit every corner of the museum. Listed below are several suggestions to help you get started. Begin here, and follow your curiosity!

The American Wing

(Please be sure to visit this area. The Englehard Court is a musst.)

Met menu

Karl Bitter, All Angels' Church Pulpit and Choir Rail (1900)

←

Louis C. Tiffany Collection

→In the American Wing, you will find a special exhibit of the art and design sketches of the famous decorative artist, Louis Comfort Tiffany.

In this exhibit, pay special attention to Tiffany's stained glass windows and lamps, which earned him popular fame. In the American Wing's Charles Englehard Court, be sure to view the entrance loggia to Tiffany's once famous mansion, now destroyed, Laurelton Hall.

Tiffany's glass, ceramics, metalwork, paintings, and fabric designs decorated the homes, clubrooms, churches, and other spaces, of America's wealthiest turn-of-the-century figures.

At right: Louis C. Tiffany, View of Oyster Bay, 1908, Leaded Favrile-glass window from the William C. Skinner House, New York City, 72 3/4 x 66 1/2 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

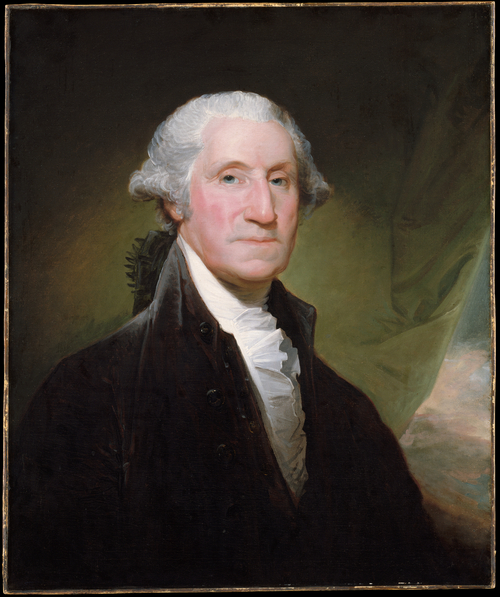

Stuart's Portrait of Washington

←"This portrait of President Washington, called the Gibbs-Channing-Avery portrait, is one of eighteen similar works known as the Vaughan group. The first of this type, presumably painted from life and then copied in all the others, originally belonged to Samuel Vaughan, a London merchant living in Philadelphia and a close friend of Washington. This original portrait by Stuart, painted in 1795 according to Rembrandt Peale, was subsequently acquired by Joseph Harrison of Philadelphia. While in Harrison's collection, Rembrandt Peale copied it many times. The version now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, considered to be one of the earliest and best replicas, was sold to Stuart's close friend, Colonel George Gibbs, and subsequently descended in the Gibbs family."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

At left: Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, Begun 1795. Oil on canvas, 30 1/4" x 25 1/4". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

William Guy Wall, New York from the Heights Near Brooklyn (ca. 1820–1823)

→NOT ON VIEW: Look for this item in the open storage area of the American Wing, on the upper level.

Edward Hicks, Peaceable Kingdom (ca. 1830–1832)

←

Francis William Edmonds, Taking the Census (1854)

→

Winslow Homer, Northeaster (1895, reworked 1900)

←

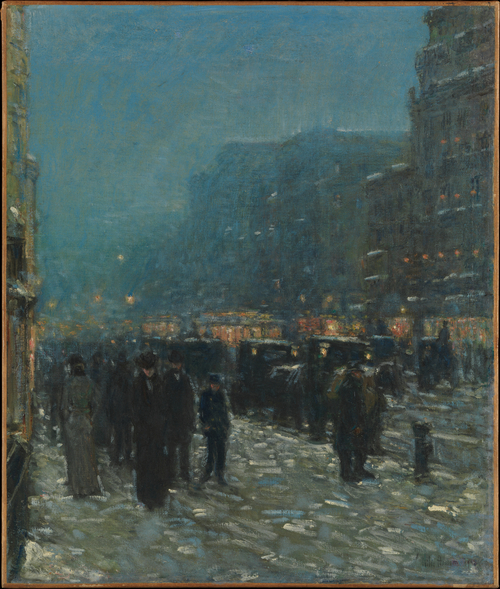

Childe Hassam, Broadway and 42nd Street (1902)

→A leading figure in late-nineteenth-century U.S. American impressionism, Hassam depicted the realities of urbanizing life in America's cities, paying special attention to New York City. Here, Hassam portrays New York's most famous thoroughfare mid-city, with the commotion and crowds of evening. How does this image compare to your experience of last week, walking through the very same intersection?

Hassam's work is also notable in its contrast to the Realist school of American painting—the Ashcan School—that followed his work, and favored stark, literal portrayals of everyday city life (e.g., see the work of Robert Henri and John Sloan).

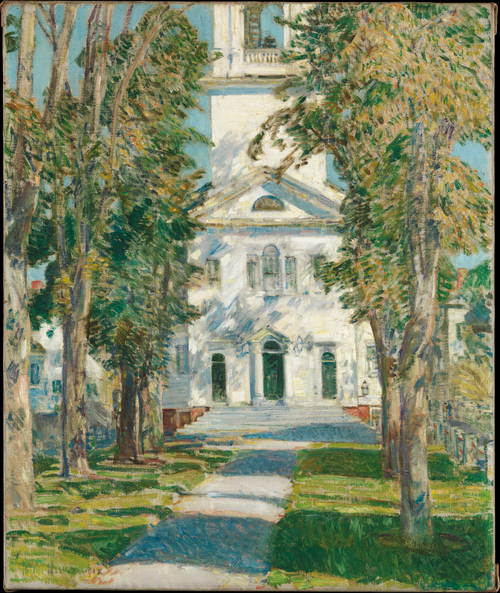

Childe Hassam, The Church at Gloucester (1918)

←Consider this painting in contrast with Hassam's Broadway at 42nd Street. Think of differences between the hot, crowded, dirty city, and the verdant grounds surrounding this pristine white edifice.

This church is the first Universalist church in America, and is often visited as a site of historical interest. The bell is still rung every Sunday for worship at 10:30 AM. It is the original bell that was cast by Paul Revere.

Items from the Cultures of Korea and Côte d'Ivoire

(these objects are required viewing)

Met menu

Arts of Korea Gallery

→One of the most substantial collections of Korean artworks outside of Asia, this decade-old permanent exhibition displays some of the rarest items in the Met's holdings.

Though not on view, this Choson dynasty painting of Water-Moon Avalokiteshvara (1730) represents the high quality of works included in the Arts of Korea gallery.

Kòmò Helmet Mask (Kòmòkun)

←"Kòmò associations create helmet masks like this one that awe audiences and reflect members' great power and knowledge. Kòmò is one of the most widespread and revered power associations across West Africa. Local chapters in the region cultivate knowledge of flora and fauna and develop the capacity to harness spiritual energy in order to counteract malevolence and help people in their daily lives. Power association leaders work with community members to address concerns related to their families, career goals, personal relationships, and health. The helmet masks kòmò associations sponsor are enhanced over time as leaders expand their knowledge.

"Sculptors carve a domed head, gaping jaws, and either large ears or long horns projecting from the back into a single piece of wood to create a wooden armature. The most knowledgeable kòmò members add diverse materials to the base the sculptor provides. The forms artists create in wood do not represent any single animal. Rather, sculptors combine characteristics of several of the most fearsome creatures in the wilderness. Elements attached to helmet masks include animal horns, tusks, porcupine quills, bird skulls, feathers, textiles, and other less readily identifiable materials, each an indication of the specific knowledge and power of the person who adds it to the wooden base. A mixture of earth, sacrificial materials, and pulverized medicinal plants coat the assemblage and increase the power associated with the mask.

"Blacksmiths are integral to the creation of kòmò helmet masks. Esteemed for their abilities to turn iron ore into usable metal and trees into wooden sculptures, blacksmiths are distinguished from other members of the community. They often live in separate quarters and marry only among themselves. Their specialized knowledge and technical abilities earn them great respect. Blacksmiths contend with dangerous and powerful spiritual forces as they transform raw materials into tools and sculptures. Their knowledge and mastery of these forces are evident in the kòmò helmet masks that combine terrifying forms in wood with potentially harmful materials to create objects that benefit individuals and the community."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Face Mask, Côte d'Ivoire, 19th–20th century

→

Masterworks of Western Art Traditions

Met menu

El Greco, The Miracle of Christ Healing the Blind (possibly ca. 1570)

→"This masterpiece of dramatic storytelling was painted by El Greco either in Venice or in Rome, where he worked after leaving Crete in 1567 and before moving to Spain in 1576. It illustrates the Biblical subject of Christ healing a blind man by anointing his eyes. The two figures in the foreground may be the blind man's parents reacting to the miracle. The gesticulating figure groups and deeply receding space reflect the artist's admiration of the great Venetian painters Tintoretto and Veronese. The upper left portion of the composition is unfinished. El Greco painted two other versions of the subject; he seems to have taken this one with him to Spain."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

El Greco, View of Toledo (n.d.)

←

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-portrait (1660)

→

Rembrandt van Rijn, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (1653)

←"This picture was painted in 1653 for the Sicilian nobleman Don Antonio Ruffo (1610/11–1678) and sent from Amsterdam to his palace in Messina during the summer of 1654. Ruffo was an avid collector; at his death he had 364 paintings, including a work by Van Dyck, 'Saint Rosalie Interceding for the Plague-stricken of Palermo', now also in the MMA (71.41). Though he went out of his way to collect works by famous masters, Ruffo rarely left Messina. He ordered this work through an agent, Giacomo di Battista, who did business with Cornelis Gijsbrechtsz, a wealthy Amsterdam merchant. Shortly after its delivery, the picture was recorded in Ruffo's inventory [see Ref. 1657] as a half-length figure of a philosopher, possibly Aristotle or Albertus Magnus. Based on this description, Giltaij concludes [see Ref. 1999] that Ruffo did not have a particular subject in mind when he made the commission, but probably asked for a half-length figure of a certain size. The dimensions given in the inventory are 8 x 6 palmi, equivalent to about 178 x 134 cm. (one palmo romano was about 22.34 cm.) and considerably larger than the current dimensions of the painting. Kirby [see Ref. 1992] explains, however, that the dimensions in palmi used in the Ruffo inventories were inexact measurements meant only as a guide. X-radiography confirms that the painting is close to, if not exactly, its original size.

"In 1660, Ruffo commissioned a pendant for the Aristotle from the Bolognese artist Guercino (1591–1666), providing him with the desired dimensions and a sketch of the Rembrandt painting. In a letter to Ruffo of October 6, 1660, Guercino notes that 'to accompany Rembrandt's which I judge to represent a Physiognomist, I thought it most fitting to make a Cosmographer . . .' Guercino's painting is now lost, but is known from a drawing in the Princeton University Art Museum.

"Ruffo also ordered companion paintings from Rembrandt. They are the 'Alexander the Great' of 1661 (now lost) and 'Homer' (Mauritshuis, The Hague), dated 1663. Both are mentioned in an invoice dated July 30, 1661. In a letter of November 1, 1662, Ruffo addressed a letter to the Dutch consul in Messina, expressing dissatisfaction with the painting of Alexander and noting that he paid more for it than for the Aristotle; that the subject was in fact Aristotle had probably been clarified for Ruffo once he commissioned the other works from Rembrandt.

"Until 1917, when Hoogewerff [see Ref.] connected the newly published Ruffo documents with this painting, the subject had been variously identified as Ariosto, Tasso, Virgil, an imaginary man of letters, philospoher, or savant, or an actual poet or scholar of Rembrandt's time, such as Pieter Cornelisz Hooft.

"Julius Held's analysis of the subject in an article of 1969 [see Ref.] is still widely upheld. According to Held, Aristotle compares "two sets of values": on the one hand, everything that he admired in Homer—gravity, humility, 'unequalled diction and thought'—and, on the other, wealth and worldly honor as embodied by the gold chain and medallion bearing what is meant to suggest an image of Aristotle's royal pupil, Alexander the Great."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Johannes Vermeer, Allegory of the Catholic Faith (ca. 1670–1672)

→"One of Vermeer's most unusual pictures, this large canvas was probably commissioned by a Catholic patron. The subject was adopted from a standard handbook of iconography, Cesare Ripa's 'Iconologia.' Vermeer interpreted Ripa's description of Faith with the 'world at her feet' literally, showing a Dutch globe published in 1618. The divine world is suggested by the glass sphere hanging overhead. The painting of the Crucifixion on the wall copies a work by Jacob Jordaens. Among the several Christological symbols, the most prominent are the apple, emblem of the first sin, and the serpent (Satan) crushed by a stone (Christ, the 'cornerstone' of the church). Dating from about 1670, the work strikes a balance between abstraction and haunting similitude."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Johannes Vermeer, Young Woman with a Water Pitcher (ca. 1662)

←"This well-preserved picture of the early to mid-1660s is characteristic of Vermeer's mature style. Notwithstanding his remarkable interest in optical effects, the artist achieved a quiet balance of primary colors and simple shapes through subtle calculation and some revision during the execution of the work. The composition suits the theme of domestic tranquility, underscored by the basin and pitcher, traditional symbols of purity. This canvas was the first of thirteen paintings by Vermeer to enter the United States between 1887 and 1919."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Johannes Vermeer, Study of a Young Woman (ca. 1665–1667)

→"This painting dates from about 1665–67, a period in which Vermeer painted two similar works: 'Girl with a Red Hat' (National Gallery of Art, Washington) and 'Girl with a Pearl Earring' (Mauritshuis, The Hague). The latter is on canvas and is nearly identical in size to the MMA picture.

"Until 2001, the MMA canvas was called 'Portrait of a Young Woman'. However, it is certain that Vermeer's bust-length pictures of young women were not intended as portraits, even if a live model was employed. In contemporary inventories, including that of Vermeer's estate, paintings of this type were called 'tronies', a now defunct term that could be translated as heads, faces, or expressions. Depicting intriguing character types and exotic or imaginary costumes, tronies were made as collectors' items; the materials depicted—such as the blue silk draped around the model's shoulders in this painting—were not secondary but essential motifs intended for the connoisseur's eye, showing the artist's powers of invention and execution.

"This may be one of three paintings by Vermeer described as "Een Tronie in Antique Klederen, ongemeen konstig" (A tronie in antique dress, uncommonly artful) in the 1696 Amsterdam auction of paintings owned by Jacob Dissius, the son-in-law and heir of the artist's Delft patron Pieter Claesz van Ruijven (1624–1674). In lighting and palette, it is very different from the Mauritshuis canvas, which employs primary colors in discreet passages and a more emphatic contrast of light and shadow. However, the similar subjects and sizes of the two works along with their complementary formal qualities may indicate that they were meant as a pair [see Ref. Liedtke 2007]."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

John Constable, Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop's Grounds (ca. 1825)

←"In 1822, John Fisher, bishop of Salisbury, commissioned John Constable to paint the version of this composition now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. (Fisher and his wife are visible at lower left in all versions of the composition). In July 1824, he asked Constable to revise it, whereupon the present canvas was begun. Infrared reflectography reveals that it started with an outline traced from the first version, and that the artist then improvised directly on the canvas, painting in the sky and opening up the foliage arching over the south transept to give the spire a more dominant role in the composition. In Constable's estate sale, this work was described as 'nearly finished.' It is indeed a study for the final version, completed in 1826 (Frick Collection, New York)."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

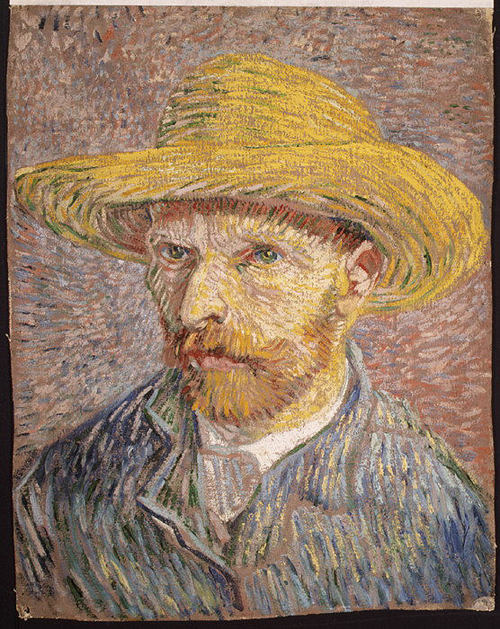

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat (1887)

→'In 1886, at age thirty-two, Van Gogh arrived in Paris "not even know[ing] what the Impressionists were." By the time he left, two years later, he had cast off the muddy palette and coarse brushwork that had characterized his earlier efforts and embraced the latest developments in painting. Here he demonstrates his awareness of Neo-Impressionist technique and color theory, using the back of a Dutch peasant study he had taken with him to Paris.

"Van Gogh produced more than twenty self-portraits during his Parisian sojourn. Short of funds but determined nevertheless to hone his skills as a figure painter, he became his own best sitter: 'I deliberately bought a good mirror so if I lacked a model I could work from my own likeness.'"

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Vincent van Gogh, Irises (1890)

←"Upon his arrival at the asylum in Saint-Rémy in May 1890, Van Gogh painted views of the institution's overgrown garden. He ignored still-life subjects during his yearlong hospital stay, but before leaving the artist brought his work in Saint-Rémy full circle with four lush bouquets of spring flowers: two of roses and two of irises, in contrasting formats and color harmonies. Van Gogh noted that in the 'two canvases representing big bunches of violet irises,' he placed 'one lot against a pink background' and the other 'against a startling citron yellow background' to exploit the play of 'disparate complementaries.' Owing to the use of a fugitive red pigment, the 'soft and harmonious' effect that he had sought in the Metropolitan's painting through the "combination of greens, pinks, violets" has been altered by the fading of the once pink background to almost white. Another still life from the series, an upright composition of roses, is on view in the adjacent gallery. Both were owned by the artist's mother, who kept them until her death in 1907."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Duccio di Buoninsegna, Madonna and Child (ca. 1300)

→Perhaps painted about 1300, this exquisite painting inaugurates the grand tradition in Italian painting of envisioning the sacred figures of the Madonna and Child in terms appropriated from real life. The parapet—among the earliest of its kind—connects the fictive world of the painting with that of the viewer. As with his younger Florentine contemporary, Giotto, Duccio has redefined the way in which we relate to the picture: not as an ideogram or abstract idea, but as an analogue to human experience.

Duccio was the founder of Sienese painting, and his influence extended as far north as Paris.

There is no record of the painting prior to its acquisition by Count Gregori Stroganoff in the late nineteenth century. The damages along the bottom of the original frame are from candles lit before the painting.

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

20th-Century American Masters

Met menu

Mary Cassatt, Young Mother Sewing (1900)

←

Jackson Pollock, Autumn Rhythm (1950)

←Jackson Pollock was born in Cody, Wyoming. Throughout his childhood, his family lived on a succession of truck farms in Arizona and southern California. When he was sixteen, Pollock first studied art at Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, where he met Philip Guston and Reuben Kadish, two friends who later became artists.

"In 1930, at age eighteen, Pollock moved from Los Angeles to New York City, settling in Greenwich Village. He immediately enrolled at the Art Students League, where he studied drawing and painting for five semesters with the American Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton, who soon became his mentor and friend.

"In 1936 Pollock joined the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros's Experimental Workshop, in New York, where he became aware of unorthodox mediums and techniques that he later adapted in his large drip paintings. In the late 1930s Pollock worked for the Easel Division of the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration.

"From 1942, when he had his first one-person exhibition at Peggy Guggenheim's Art of This Century gallery in New York, until his death in an automobile crash at age forty-four in 1956, Pollock's volatile art and personality made him a dominant figure in the art world and the press. In 1947–48 he devised a radically new innovation: using pour and drip techniques that rely on a linear structure, he created canvases and works on paper that redefined the categories of painting and drawing. Referring to his 1951 exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery, fellow Abstract Expressionist painter Lee Krasner, who was Pollock's wife, noted that his work 'seemed like monumental drawing, or maybe painting with the immediacy of drawing—some new category.'

"Pollock's poured paintings are as visually potent today as they were in the 1950s, when they first shocked the art world. Their appearance virtually shifted the focus of avant-garde art from Paris to New York, and their influence on the development of Abstract Expressionism—and on subsequent painting both in America and abroad—was enormous.

"To many, the large eloquent canvases of 1950 are Pollock's greatest achievements. "Autumn Rhythm," painted in October of that year, exemplifies the extraordinary balance between accident and control that Pollock maintained over his technique. The words "poured" and "dripped," commonly used to describe his unorthodox creative process, which involved painting on unstretched canvas laid flat on the floor, hardly suggest the diversity of the artist's movements (flicking, splattering, and dribbling) or the lyrical, often spritual, compositions they produced.

"In 'Autumn Rhythm,' as in many of his paintings, Pollock first created a complex linear skeleton using black paint. For this initial layer the paint was diluted, so that it soaked into the length of unprimed canvas, thereby inextricably joining image and support. Over this black framework Pollock wove an intricate web of white, brown, and turquoise lines, which produce the contrary visual rhythms and sensations: light and dark, thick and thin, heavy and buoyant, straight and curved, horizontal and vertical. Textural passages that contribute to the painting's complexity—such as the pooled swirls where two colors meet and the wrinkled skins formed by the build-up of paint—are barely visible in the initial confusion of overlapping lines. Although Pollock's imagery is nonrepresentational, 'Autumn Rhythm' is evocative of nature, not only in its title but also in its coloring, horizontal orientation, and sense of ground and space."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Edward Hopper, Tables for Ladies (1930)

→"Tables for Ladies places the viewer directly outside the front window of an ordinary restaurant in New York City. The viewer's gaze is directed past the menu cards and the vividly painted foods in the window display and the waitress who leans forward to adjust them, into an interior of polished wood, tiled floors, and wall mirrors where a man and woman eat and a cashier attends to business at her register. Hopper painted this large canvas in the studio, working from sketches that he had made of local restaurants. Yet despite the bright lighting and the warm, even garish, colors, this is not a particularly festive scene. The two diners chat between themselves, but the cashier and the waitress are lost in their separate thoughts and duties. As in many of his works, Hopper indirectly comments on the loneliness and weariness that so many city dwellers experience.

"Despite Hopper's reluctance to assign historical context to his work, this painting also speaks of several social changes of the era. For example, it represents the new roles that women were occupying in public; both the cashier and the waitress, for example, are women working outside the home. The title also alludes to a recent social innovation, in which dining establishments advertised "tables for ladies" in order to welcome their newly mobile female customers. In the past, it had often been assumed that women appearing alone in restaurants or bars were prostitutes in search of business; now, dining on their own or with other women, they would be treated respectfully. In addition, the date of this painting serves as a reminder that Hopper was living in New York during the Great Depression, when many Americans could not afford to dine out, even at such an unpretentious establishment as this one."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Roy Lichtenstein, Stepping Out (1978)

←"To many people, Roy Lichtenstein's paintings based on comic strips are synonymous with Pop Art. These depictions of characters in tense, dramatic situations are intended as ironic commentaries on modern man's plight, in which mass media—magazines, advertisements, and television—shapes everything, even our emotions. Lichtenstein also based paintings on well-known masterpieces of art, perhaps commenting, as did Andy Warhol in his 'Mona Lisa,' on the conversion of art into commodity. Like Warhol, Lichtenstein, who had an art-school background, also worked as a commercial artist and graphic designer (1951-57), an experience that influenced the subject matter of his later paintings. Lichtenstein's fame as a Pop artist began with his first one-man exhibition, at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York in 1962, and continued to characterize his career throughout his life.

"'Stepping Out' is marked by Lichtenstein's customary restriction to the primary colors and to black and white; by his thick black outlines; and by the absence of any shading except that provided by the dots imitating those used to print comic strips. Yet beneath the simplicity of means and commonplace subject matter lies a sophisticated art founded on a great deal of knowledge and skill. Lichtenstein here depicts a man and woman, side by side, both quite dapperly dressed. The male is based on a figure in Fernand Léger's painting 'Three Musicians' of 1944 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), but seen in mirror image. He wears a straw hat, high-collared shirt, and striped tie; the flower in his lapel is borrowed from another Léger painting. The female figure, with her dramatically reduced and displaced features, resembles the Surrealistic women depicted by Picasso during the 1930s. Her face has been reduced to a single eye set on its side, a mouth, and a long lock of cascading blond hair.

"The composition of 'Stepping Out' is complex and rather elaborate. The figures, while quite different in appearance and style of dress, are united through shape and color: the sweeping curve of the woman's hair is answered by the curve of her companion's lapel; the diagonal yellow of the end of her scarf is echoed in the yellow rectangle that covers the top of his face; the red Benday dots cover half of both faces; and the black that serves as background for the man invades the area behind the woman."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Andy Warhol, Self-portrait (1986)

→"Of all the Pop artists who emerged in New York and on the international scene in the early 1960s, none is more famous or more typifies the movement than Andy Warhol. Although he had a traditional art education at Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, as a young man in the 1950s he supported himself doing commercial art in New York. About 1959 he decided to concentrate his energies on painting, calling upon both his formal training and commercial experience in his new work.

"Warhol purposely sought an alternative to the emotionally charged paintings of the Abstract Expressionists by adopting a commercial, hands-off approach to art. His aim was to demystify art by making it look as if anyone could have done it. To this end, he borrowed images from American popular culture and celebrated ordinary consumer goods, such as Brillo pads, Campbell's soup cans, and Coca-Cola bottles, as well as media and political personalities, including Marilyn Monroe and Mao Zedong. He featured them in individually colored serial paintings and prints that relied on commercial silkscreening techniques for reproduction.

"After the early 1960s his most frequent subjects were the famous people he knew, and occasionally he was his own subject. In this eerie, premonitory self-portrait, produced just a few months before his death in February 1987, Warhol appears as a haunting, disembodied mask. His head floats in a dark black void and his face and hair are ghostly pale, covered in a militaristic camouflage pattern of green, gray, and black."

—The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Special Exhibits: Group Assignment

(you are required to view only one of the following three exhibits)

Met menu

Tutankhamun's Funeral

description | object list

Celebration: The Birthday in Chinese Art

description | object list

Epic India: Scenes from the Ramayana

description | object list